By Doug Bernst

As a student and a teacher in Thunder Bay, I have seen Remembrance Day transition from a statutory holiday to a day of solemn ceremonies marked by assemblies and honour guards to an announcement over the intercom with a moment of silence accompanied by a recorded trumpet solo. While I don’t know if this represents deterioration in the respect we have for this day, I suspect it does.

I do know, however, that Remembrance Day has always been a day of significance to me, largely because my father was a veteran of World War II and from a young age I felt pride in that knowledge. But as I grew older, I also developed a sense of wonder at how a Saskatchewan farm boy who had to look hard for a pond deep enough to swim in ended up enlisting in the navy; who, at the age of 19, spent the next three years of his life sailing across the North Atlantic (arguably the most treacherous stretch of water in the world) in a corvette, a ship that was little more than a distraction and a target for German U-boats to prevent them from attacking the more valuable cargo and troop ships.

Now, as we approach Remembrance Day, and people begin to pin poppies to their lapels, thoughts turn to the sacrifices made by Canadian military personnel and their families over the course of the history of our country. It is the sacrifice of those families—and, in fact, one particular family—that is the focus of this story.

Almost every Remembrance Day ceremony involves laying of wreaths as a recognition of sacrifices made by Canadian military personnel. At the national ceremony in Ottawa, one of those wreaths is delivered by the National Silver Cross Mother. The National Silver Cross Mother is the recipient of the Memorial Cross (Silver Cross), which is granted by the Canadian government as a memento of personal loss and sacrifice in respect of military personnel who lay down their lives for their country. In 1985, that honour was bestowed upon Thunder Bay’s own Mrs. Rose Alice Louise Bernst, my grandmother.

National Memorial (Silver) Cross Mother, Rose Bernst

Rose’s story begins as a familiar one to many Canadian families. Born in London, England in 1898, she immigrated to Canada at the beginning of the 20th century. She met Edward Bernst in Fort William (now Thunder Bay), married, and moved to Nokomis, Saskatchewan, where they had a family of eight children—seven boys and one girl. They were unable to keep their farm when the Great Depression hit during the 1930s, and moved back to Thunder Bay (Murillo) in 1935. I will admit a certain bias with regards to the next part of this story, but I believe the advent of World War II in 1939 marked the beginning of one of the most remarkable stories of family sacrifice in Canadian history. The story of my father and my uncles often reminds me of Steven Spielberg’s sensational war epic Saving Private Ryan.

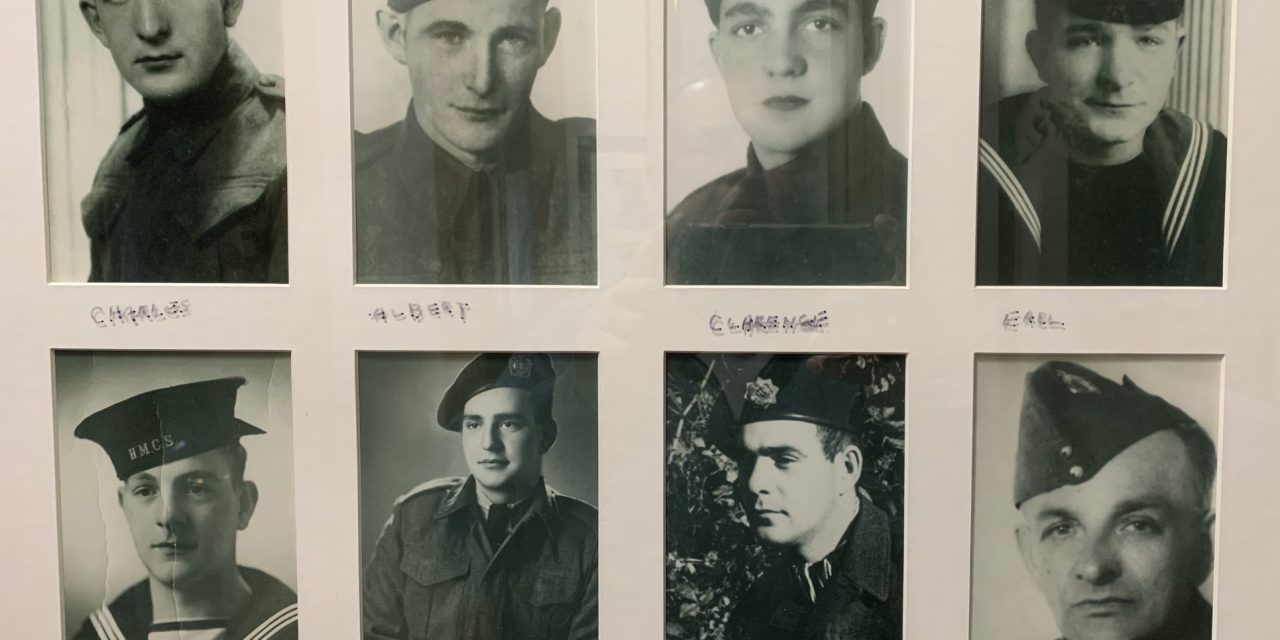

The premise of the movie is the need to locate and return home the titular character to prevent further grief for his mother, who lost three other sons in the D-Day invasion. If the writers of this film had been looking for something more realistic, they might have been well served by researching the story of Rose Bernst and her family. Rose had the unique distinction of having all seven of her sons and her husband serve in the Canadian Armed Forces: her husband Edward served with the Forestry Corps in Scotland from 1942–1945, her sons Clarence and Charles served with the Lake Superior Motor Regiment, Albert served with the British Columbia Dragoons, Harry with the Princess Patricia Light Infantry, Ronnie and Earl with the Royal Canadian Navy (all during WWII), and Allan, the youngest, served in Korea from 1954–1957.

Tragically, Ronnie and Clarence did not return from service during WWII. Clarence died in 1941 from injuries while serving with the Lake Superior Motor Regiment and Ronnie was killed at sea when the corvette Shawinigan was torpedoed in 1944. It was for the loss of these two sons that Rose was awarded the Silver Cross in 1985, but the sacrifices of the rest of her immediate family are no less significant. I remember my grandmother was reluctant to go to Ottawa to lay the wreath at the National War Memorial. In part she was intimidated by the thought of meeting Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and having tea with Governor General Jeanne Sauvé, but I believe her reluctance was mostly because the memory of losing two sons still weighed heavily upon her. I suspect it was for this reason that she didn’t talk much about the war. Neither did my father.

Remembrance Day has taken on additional significance for me, as it marks the anniversary of the passing of my father in 2019—the last in his family. But as always, when I pin that poppy to my lapel, I will continue to think of him at the age of 19 sailing the North Atlantic. I will also remember my grandfather, and the uncles that I knew and the ones that I never met. But I will also remember my Aunt Bernice and my grandmother Rose, who had to watch them all leave that farm in Murillo, at a time when the world very well might have been at its very worst, and I will think of how hard that must have been for them.