A Music Icon Talks About His Roots in Thunder Bay

By Bonnie Schiedel

Paul Shaffer is one of music’s cool guys. He’s played with pretty much every legend you can think of and has racked up a mightily impressive, decades-long musical CV. So when we were planning our annual music issue, of course we had to include Thunder Bay’s homegrown hero.

One of Shaffer’s earliest memories is sitting under his family’s grand piano, listening to his mom Shirley play Chopin and Gershwin. “My mother made sure that I got started on lessons: ‘that kid is gonna play the piano if it’s the last thing I do,’ was her attitude,” says Shaffer in an October phone interview with The Walleye. So he began his formal musical training by biking over to lessons with Mrs. Hardy on Catherine Street, and the occasional recital at the Shaarey Shomayim synagogue on Grey Street.

The first time he heard rock and roll on the radio, he knew music was going to be important in his life. “I sure remember a R&B song called “A Hundred Pounds of Clay” by Gene McDaniels; hearing that on the radio and it reaching me somehow,” he says. “I wanted to figure out how to play that song on the piano and I did, then that started me on trying to figure out how to play songs by ear from the radio. And I’m still basically doing that.” More than 50 years later, Shaffer easily rattles off the call signs for three local radio stations in the 1950s and 60s: “CKPR, CJLX, and CFPA: Serving the Lakehead.”

In his early high school years he discovered he could tune in to American radio stations at night, thanks to some quirk of physics. “I could hear WLS Chicago after dark, and that was like a lifeline to what was happening in the U.S.A. And then I found a station from Little Rock, Arkansas that played all soul music and rhythm and blues after midnight. I was tired in a lot of those geography classes at FWCI.” He realized that rather than music-lesson Mozart, he could play a top-of-the-charts hit like the surf-rock “Pipeline” by The Chantays at school assemblies—much to the delight of his classmates.

It was at Fort William Collegiate Institute he met fellow musician Ricky Lazar, who was a drummer in a band called The Fugitives (band leader Bobby Anuik was on vocals and guitar, Ian Rosser on guitar). For the next five years, The Fugitives played covers at high school dances all over town on Friday nights and at the Gardens on Saturday nights. “They would put the plywood down on the ice and put up a stage and we’d have a dance,” Shaffer says. “There wasn’t exactly a coat check facility going on at the Gardens, so kids would just keep their coats on, often ski jackets…it’s kind of hard to be cool when you’re bundled up for winter.” And it was as a teenager in the audience watching The Guess Who lift the roof (in the days before they wrote their own material) that Shaffer realized his love for cover songs. As he writes in his book We’ll Be Here for the Rest of Our Lives, “…to cover is to pay tribute to the original artists who gave your psyche a deeper shade of soul. To cover them is to love them.”

After getting his sociology degree at the University of Toronto in 1971 (thesis topic: the subculture of avant garde musicians) Shaffer’s dad Bernie gave him a year to make a go of it in music before enrolling in law school and returning home to practice with him in Thunder Bay. Just before the cut-off date, Shaffer landed the music directorship of a Toronto production of Godspell, with Eugene Levy, Gilda Radner, and Martin Short, with whom he became lifelong friends. Other stellar gigs followed in the 1970s and 80s in Toronto, New York, and LA, including being musical director for The Blues Brothers and a long stint in the house band at Saturday Night Live (where Shaffer made TV history as the first person to say “fuckin’” on live TV—it slipped out during a medieval skit where he was supposed to be saying “floggin’”), as well as playing a promoter in This is Spinal Tap and co-writing the disco hit “It’s Raining Men.”

When David Letterman’s team called to ask him to be the music director when Late Night started up in 1982, they said he could only have four musicians in his band, and Shaffer knew that fit right in with his early musical collaboration with The Fugitives. “I knew what the bass should do, I knew what the drums should do. I knew how to arrange for a rhythm section of a four-piece band: piano, bass, drums, guitar. It was perfect for me.” For 33 years, Shaffer was the bandleader and musical director who bantered with Letterman and rocked the house four nights a week with The World’s Most Dangerous Band.

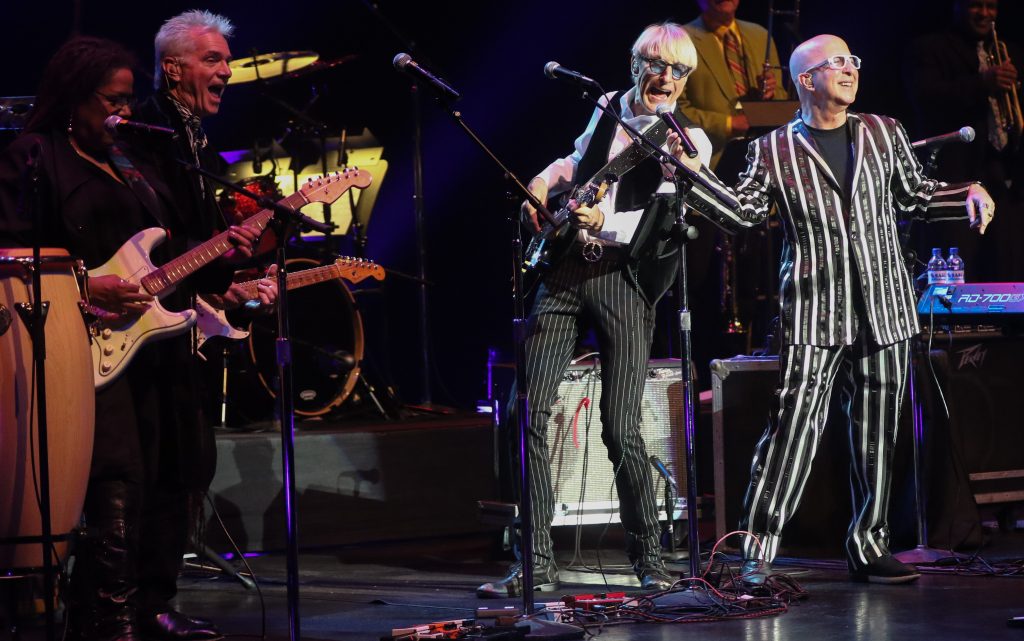

When the show wrapped in 2015, Shaffer moved on to some new projects, including being the incognito Skeleton on The Masked Singer, doing a cameo on Schitt’s Creek, playing and recording with The World’s Most Dangerous Band, doing mini-residencies at Caesar’s Palace in Vegas, composing for My Next Guest Needs No Introduction with David Letterman, and putting together the musical arrangements for large orchestral shows (he was scheduled to play with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra before those plans were derailed by COVID-19).

In 2019, Shaffer took his turn in the host’s chair with Paul Shaffer Plus One on SiriusXM and AXS TV. He says he always wanted to do a show where he and a musician could get in a studio with a piano and guitars, and talk and play music as it came up in the conversation. “I got to do nine episodes with a lot of really great people like Smokey Robinson—I don’t mind telling you, that may have been my very favourite of all of them—[and] greats like Sammy Hagar, Joe Walsh, Billy Gibbons from ZZ Top, Martin Short, who is not exactly a rock and roller, but he did it as well. And I’m very proud of those shows.” He hopes to continue with the satellite radio version when pandemic restrictions loosen up.

Through it all, Shaffer has been having a blast. “If performers aren’t having fun, how can you expect the audience to have fun?” he asks. Certainly, of course, there are times when you’ve got the flu or heartburn, you have to power through and be professional, he says. “However, most of the time, it is just truly a blessing to get to do it: to play with other people, the experience of what that is like is out of this world. I don’t take it for granted, I haven’t soured on it…Every time I get to play with a musician is really good.”