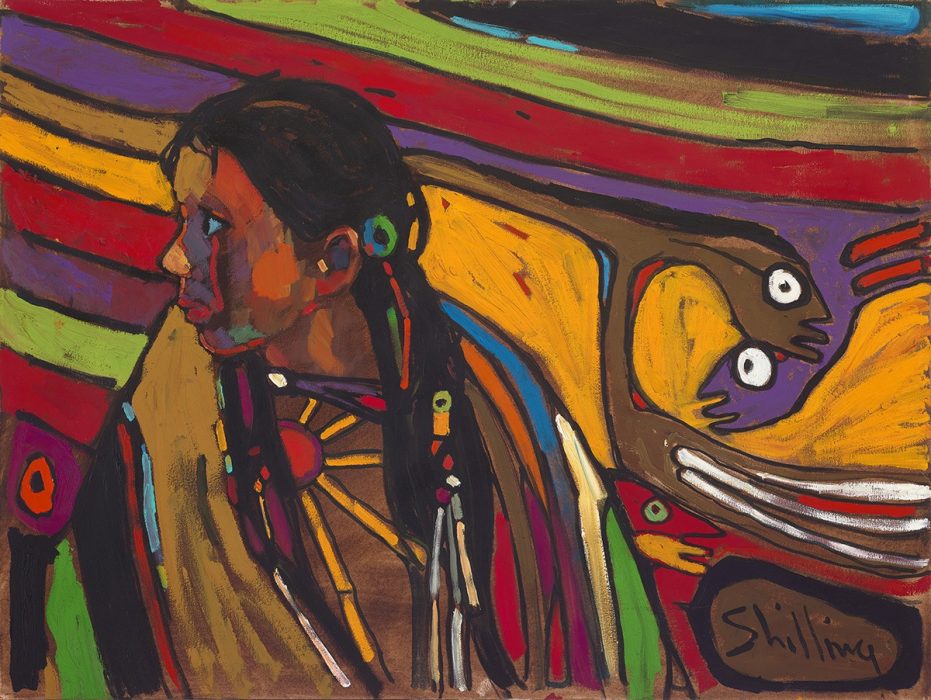

Piitwewetam: Making Is Medicine Featured at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery

By Jolene Banning

Five years ago, Shannon and Ryan Gustafson heard the news no parent ever wants to hear: that their first-born son Jesse had died in a car accident. The family was devastated. It didn’t feel right to plan a funeral in a Western way, using a church service. “Colonialism has really impacted the way we grieve. It’s like we don’t know how,” says Shannon. So they turned to Anishinaabe ceremony and art. Five years later, with nearly 50 pieces that one would use in ceremony, the family is opening Piitwewetam: Making Is Medicine, an exhibit that features their grief and grieving process. It’s an exhibit about honouring Jesse’s life.

The Gustafsons have always been closely tied to the powwow community, and are well known across Turtle Island for their beadwork, textiles, and regalia. When they were first hit with the tragic news, Shannon took the project she was working on—a tikinagan—and tossed it in a black garbage bag and threw it in her closet. She couldn’t imagine working on anything, let alone a baby carrier—the same kind her youngest was held in as a baby—so she started looking for resources to help with her grief. “[As] Indigenous people, we are naturally spiritual beings because we have that connection to the land, to the water, to the stars and all of creation,” she says.

Their spiritual advisor and friend, Ron Mandamin, guided them through their son’s ceremony and helped them understand the journey Jesse is on according to Anishinaabe understandings of the afterlife. It was while in ceremony that Shannon felt closest to her son, knowing he might not be with her physically but is always with her spiritually, and that it is while in ceremony that she is most connected to her son. It was a feeling and knowledge she needed her whole family to experience. Her husband Ryan has always been by her side while creating and in ceremony. Together they needed to connect as a family with their daughters and son in ceremony, so their creating shifted to a planned and focused night of art and items.

Together, Shannon, Ryan, and their two daughters created pieces that were true to Anishinaabe history and culture with florals, patterns, and motifs. “I strive to maintain this spiritual connection to my son and I do it through ceremony and it’s done with my family and it’s really beautiful,” says Shannon. The items the family created are pieces that can be used in ceremony, like tobacco pouches or midewin (medicine society) sash.

The curators, twin sisters Leanna (Giizis Soon Ikwe) and Jean Marshall, come from the community of Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation but call Animikii-wiikwedong (Thunder Bay) home. This exhibit is very personal to the sisters, who are also close friends with the Gustafson family. “As Anishinabeg, there isn’t always space created to grieve. We all carry different losses and there’s a lot of losses in our communities,” explains Leanna. “It’s about one family’s journey but within that family’s journey, they’re showing and teaching us how making and staying together as a family is important when we’re grieving, and the role of ceremony.”

A lot of strength comes from ceremony; creating the space for it is going to show others that there is another way to grieve that doesn’t have to be self-destructive or lonesome, or something you have to do on your own. “The one thing that deep down inside that I think about is that I feel invincible because nothing will ever, ever hurt me the way I’ve been hurt already,” says Shannon.

Piitwewetam: Making Is Medicine is scheduled to run until April 18 at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery. Visit theag.ca for updates on the gallery’s status during COVID-19.